Sections

- Neoclassical Tradition

- 19th-Century Travel

- Queen Zenobia's Legacy

Back to top

Cite this exhibition

Exhibition URL: www.getty.edu/palmyra

Cite this page

Terpak, Frances; Bonfitto, Peter Louis, The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra, Rediscovery of Palmyra,

accessed ,

https://www.getty.edu/research/exhibitions_events/exhibitions/palmyra/rediscovery.html

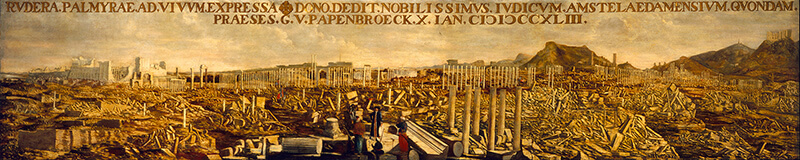

Travel to Palmyra by Europeans began with the historic 1691 expedition undertaken by British merchants based in Aleppo who, upon hearing stories about this vast ruin, made the dangerous journey across the desert. Working for the British Levant Company, several members of the group were Oxford-educated orientalists and antiquarians seeking to identify this mysterious city. Their detailed report sent to the Royal Society was later published with a 180-degree panorama that, when read from left to right, served as a virtual illustrated guide to their itinerary through Palmyra's ruins. The panorama was subsequently reproduced by Abednego Seller in his 1696 book, The Antiquities of Palmyra.

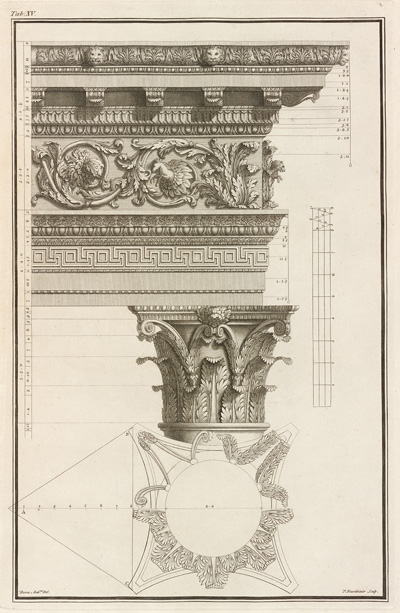

These early descriptions of a fabulous ancient metropolis bordered by a stretch of grand, monumental tombs attracted the attention of other Western scholars and travelers, who visited the site and reported on Palmyra's distinctive style blending Greco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian influences. But it was the 1753 folio volume The Ruins of Palmyra, with its abundant illustrations and informative text, published in both English and French by the renowned classical scholar Robert Wood, that seized the learned public's imagination. Palmyra's noble ruins and opulent decoration had a profound influence on classical taste, particularly in England.

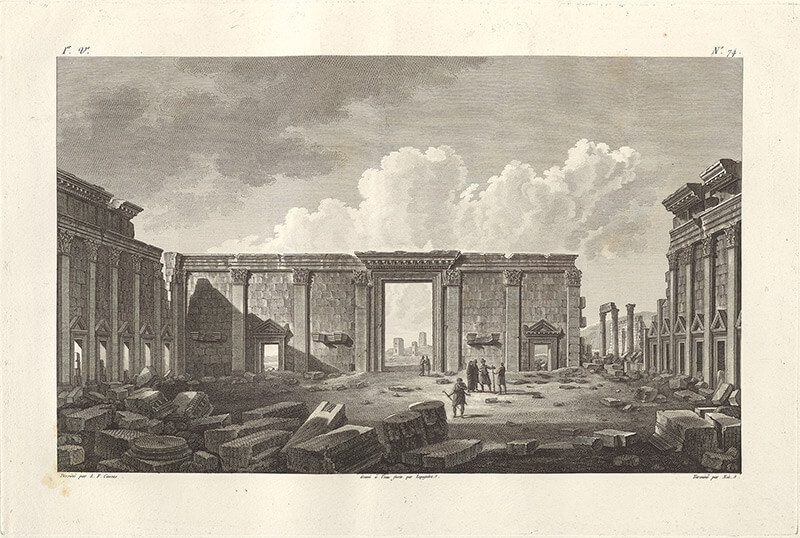

In the spring of 1751, British antiquarians Robert Wood (ca. 1717–1771) and James Dawkins (1722–1757), with the Italian draughtsman Giovanni Battista Borra (1713–1770), reached Palmyra via Beirut and Damascus. Intending to "rescue from oblivion the magnificence of Palmyra," Wood and Dawkins copied inscriptions and measured the ruins as Borra made numerous detailed sketches. The trio repeated this process at the great site of ancient Baalbek in modern-day Lebanon before returning home.

On their return to England, Wood (with financial support from Dawkins) immediately began working on publishing their findings. Borra's drawings were transformed into engravings and Wood wrote supporting text. Hailed in its day, The ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tedmor, in the desart (1753) inspired and facilitated the creation of new artworks. Architectural ornamentation was an obsession for many artists at this time. Images of well-known Italian monuments had been in circulation for decades following the popularity of the Grand Tour, but with the introduction of Wood's book, building facades, interiors, decorative arts, and paintings in England and Western Europe started to mimic the art and architecture of Palmyra.

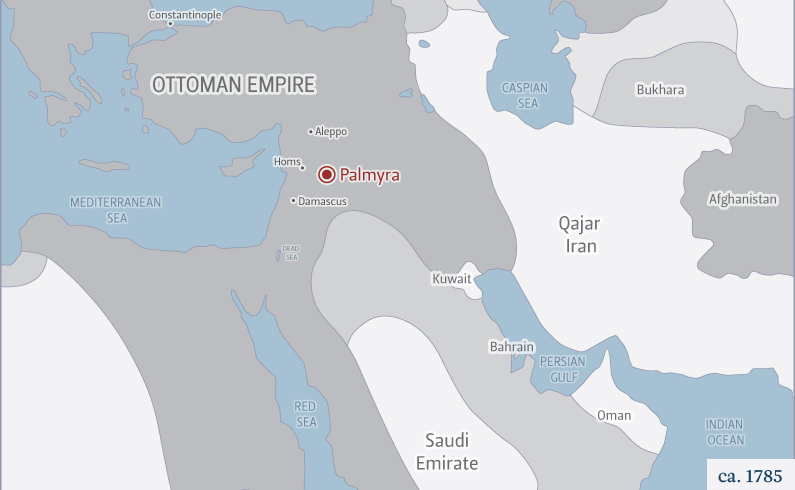

By bringing Palmyra into the purview of Western antiquarians, Wood's publication lured more travelers to the site. It was 30 years later that the architect Louis-François Cassas was commissioned by the French ambassador to the Ottoman court to record the monuments visited on his trip to the Levant from 1785 to 1787. Like Wood's publication, Cassas's was intended for an elite audience who could afford this lavish three-volume work sold by subscription and comprising hundreds of large-format plates. But with the upheaval of the French Revolution (1789–99), the project was never fully realized and prints made after Cassas's drawings were only produced in a limited number.

An interconnection between Palmyra and the French Revolution is also seen in the work of the orientalist and philosopher Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, comte de Volney (1757–1820), a contemporary of Cassas who also traveled to Syria in the 1780s. Volney's seminal political treatise, The Ruins, or Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires (1791), sets Palmyra as the exemplar for the decline of great civilizations, an imperative topic in the revolutionary period and one that shaped the formation of new governments.

Zoom not available

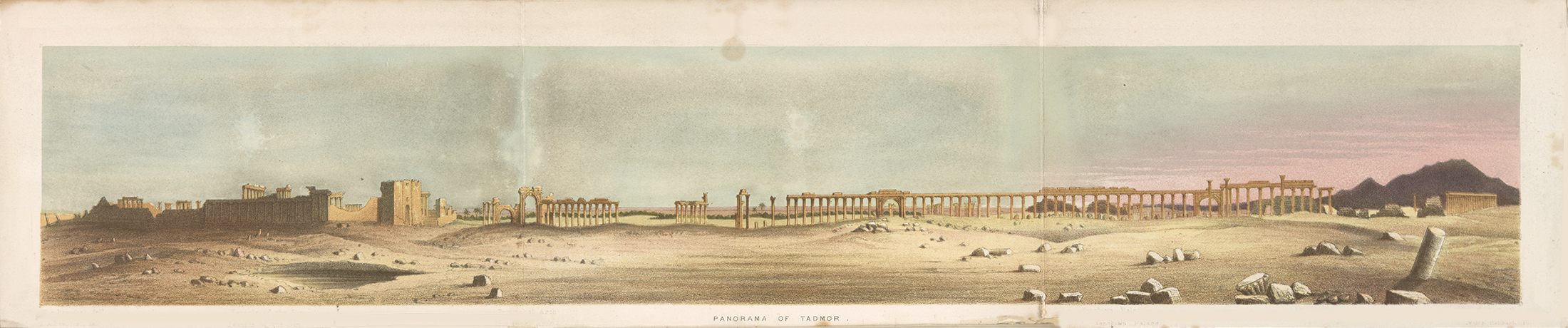

The transition from an 18th century aristocratic audience to a more literate public in the 19th century broadened knowledge about antiquity, sparked by the expansion of Western colonialism in the Middle East, which likewise contributed to new forms of travel narratives. For Palmyra, a prime example of this popular literature is Egyptian Sepulchres and Syrian Shrines, written in 1862 by Emily Anne Smythe, Viscountess Strangford, who wrote and illustrated what she described as an armchair adventure for those who could not visit Palmyra. In fact, her book was reviewed by the diplomat and scholar who subsequently became her husband. Lady Strangford's poetic evocations of the beauty of the desert's colors, the magnificence of the sun-drenched ruins, and the curious habits of the "Bedoueen" guides found a large audience. Indeed, she wished to encourage women to undertake the journey and to alert them to the safety of travel in this region. While the text often reflects 19th-century Christian-centric values and a classical bias, Viscountess Strangford clearly was enchanted by Palmyra. She wrote:

I was once asked whether Palmyra was "not a broken-down old thing in a style of slovenly decadence?" It is true its style is neither pure nor severe: nothing over which the lavish hand of hasty and Imperial Rome has passed is ever so: but, Tadmor [Palmyra] is free from all the vulgarity of real decadence; it is so entirely irregular as to be sometimes fantastic; the designs are overflowing with richness and fancy, but it is never heavy: it is free, independent, bizarre, but never ungraceful; grand indeed, though hardly sublime, it is almost always bewitchingly beautiful. (pp. 239–40)

In contrast to the widespread audiences who enjoyed Lady Strangford's adventurous text and images of Palmyra, the photographs of the site by Louis Vignes, featured in this exhibition, reached a limited audience because they were never disseminated. Nonetheless, Vignes's trip marks the beginning of modern documentation of Palmyra, and a new era of visual reportage.

For 18 centuries the classical and early Arabic texts that reference Palmyra and, most notably, those which recount tales of its fabled Queen Zenobia, have inspired artists, poets, playwrights, and novelists to reinterpret or reinvent Palmyrene history. Famous for her intellect and beauty, and with enough political acumen to raise an army against the Roman Empire in 269 CE, Zenobia has become the embodiment of Palmyra throughout the ages. Blurring the lines between fact and fiction in Zenobia's biographies began in antiquity; some sources recount that she claimed ancestry to both Dido of Carthage and Cleopatra the VII of Egypt. The differing narratives of her accession to power, conquest of imperial cities, and ultimate demise provide a field of possibilities for creative works to moralize or sensationalize her life.

Queen Zenobia has been portrayed in the works of Giovanni Boccaccio (Concerning Famous Women), Chaucer (The Monk's Tale), Pedro Calderón de la Barca (La gran Cenobia), French neoclassical tragedies (Crébillon's Rhadamiste et Zénobie), operas by Handel (Radamisto) and Rossini (Aureliano in Palmira), romantic novels by William Ware (Zenobia; or, The Fall of Palmyra) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (The Blithedale Romance), and many other literary works in diverse languages from the Middle Ages to the present day. As a subject in the visual arts, Zenobia has played the role of the forceful heroine, ideal beauty, or deposed empress. Commonly, she is depicted as a captive, as Zenobia was reportedly brought back to Rome after her defeat in "golden chains."

The popularity of Zenobia has, in some cases, led to ancient Palmyrene portraits or even sections of the city to be incorrectly, or unverifiably, associated with the warrior queen. The only confirmed depictions of Zenobia from antiquity come from the few coins she struck during her brief rule. The modern state of Syria reproduces the images from these coins on its currency. In an act of defiance against ISIS militants, a statue of Zenobia was erected in Damascus in 2015.

Next

Palmyra in the Modern Era

Previous

Ancient Palmyra

Banner image: