Sections

- Trade

- Inscriptions

- Religion

- Funerary Sculpture

- Roman and Later Periods

Back to top

Cite this exhibition

Exhibition URL: www.getty.edu/palmyra

Cite this page

Terpak, Frances; Bonfitto, Peter Louis, The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra, Ancient Palmyra, accessed

,

https://www.getty.edu/research/exhibitions_events/exhibitions/palmyra/ancient_palmyra.html

When Cassas visited Palmyra in 1785, and Vignes nearly 80 years later, they experienced an ancient site that still stirred emotions more than a dozen centuries after its downfall. Positioned at a crossroads, Palmyra was a nexus of ideas and innovations streaming from east and west that made it one of the most cosmopolitan centers in antiquity. Sometimes referred to as Roman-Baroque, the unique style of Palmyra's architecture and sculpture reveals a diverse blend of influences.

Extending some three kilometers, the vast ruins attest to Palmyra's prominence during the 1st to 3rd century CE, particularly the city's expansion from the mid-2nd century, when many of its magnificent buildings were erected. Both Cassas and Vignes employed panoramic vistas to capture the magnitude of this tumultuous ruined landscape, which they complemented with architectural details to record the singularity of the monuments. This section outlines the factors that contributed to Palmyra's rise in power and the salient features characterizing its unique culture.

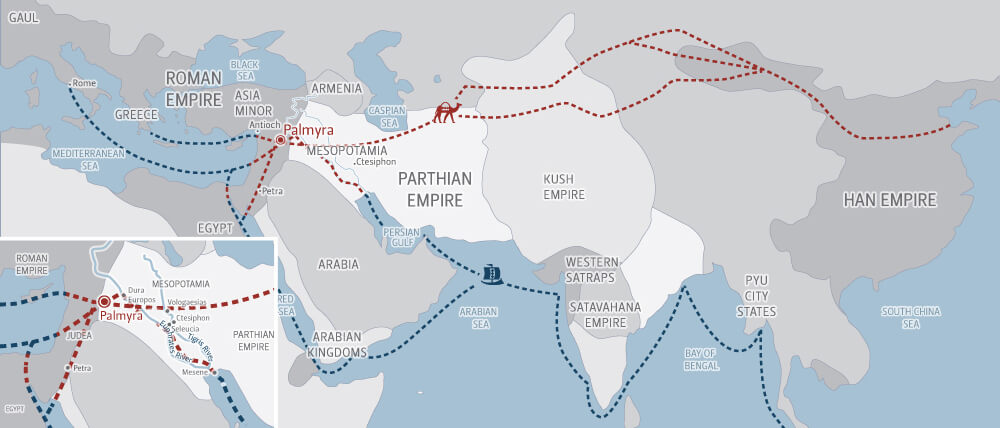

Palmyra's growth and artistic style resulted from its economic prosperity as a caravan city and its location at the eastern edge of the Roman Empire. Though under Roman influence since the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE), according to Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), Palmyra positioned itself politically between the Roman and Parthian empires. Surprisingly, the only ancient author to record its prominent role in the caravan trade is Appian. Writing in the mid-2nd century CE, he describes the attack on Palmyra in 41 BCE by the forces of Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) before shifting to the present tense: "For being traders they bring goods from [the territory of] the Persians and dispose of them in that of the Romans."

The importance of trade to Palmyra's urban development is recorded on a tariff stele (upright stone slab) erected in the agora in 137 CE, housed today in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. The stele lists, among other services, the tax for certain goods brought into and out of the city. Chiseled in two languages, local Palmyrene (an Aramaic dialect) and Greek, the tariffs distinguish among goods carried by camel, donkey, or donkey cart. While scholars have argued that the stele references, more generally, a vibrant local trade rather than a long-distance one, the citation of myrrh, bronze statues, and slaves affirms that goods were coming from afar. The most abundant evidence for Palmyra's role in long-distance trade comes from over 40 inscriptions dating between 19 and 270 CE that honored leaders and supporters of the caravan trade.

These inscriptions show how Palmyra reached its heyday in the mid-2nd century with a regular caravan trade east to Dura-Europos on the Euphrates, from where goods traveled downriver to the Persian Gulf, and ultimately could be shipped to the Arabian Peninsula or northwest India. The inscriptions also reveal that Palmyrene traders were established in Seleucia on the Tigris, in Vologaesias on the middle Euphrates, and in Mesene at the head of the Persian Gulf; in other words, in Mesopotamia, well outside Roman territory. Though it is unclear how far beyond the western Indian coast goods came from or reached East Asia, the 2,000 silk fragments originating from Palmyra's tombs signal a long-distance eastern trade, while the hundreds of bronze statues that once decorated the city and its monuments indicate Palmyra's proven ties to the Roman West.

Zoom not available

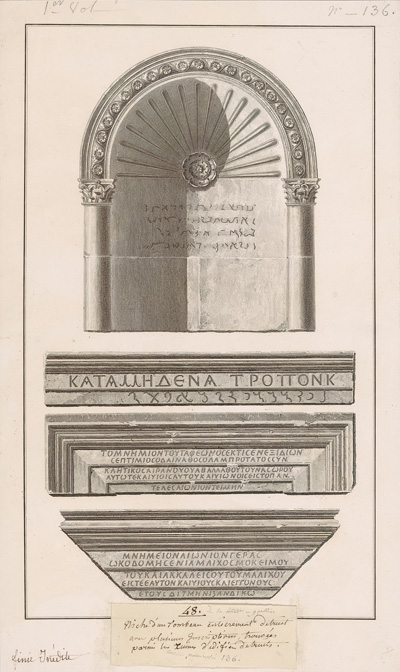

Throughout the Roman Empire, Palmyra stands apart for its distinctive language. About three thousand dedicatory, commemorative, and sepulchral inscriptions, written in Palmyrene script, have been found scattered among the ruins. These texts are the primary documents that attest to Palmyra's cultural, social, and economic position in the ancient world. A few hundred of these inscriptions are bilingual, Palmyrene and Greek, used in both civic and funerary contexts. A few are also trilingual, incorporating Latin, and thus underscore the Roman presence in the city.

Palmyrene is an Aramaic language, related to Hebrew and Nabataean, that was actively in use from the 1st century BCE to the decline of the city-state in the later 3rd century. The disappearance of the language in the late 3rd century coincided with Emperor Aurelian's conquest of the city in 273 CE, when it was garrisoned by Roman troops, suggesting that the language was willfully suppressed by the empire. Examples of mid-2nd- to early 3rd-century Palmyrene inscriptions found in such distant places as the trade route along the Euphrates in Mesopotamia and South Shields on the River Tyne in Roman Britain show the high regard for the city and the independent character of its people.

Beginning with the earliest explorers to visit Palmyra in the late 17th century, knowledge about the site was transmitted not only through written reports but also transcriptions of the numerous inscriptions scattered throughout the ruins. Because of its similarities to other Aramaic scripts, the Palmyrene language had been deciphered as early as 1754 (two decades before Cassas's visit to the site) by European scholars who had the advantage of comparing Palmyrene texts to their Greek counterparts in many bilingual inscriptions. By the middle of the 19th century, the number of recorded inscriptions merited a publication that appeared in French, with the mandate to transcribe and make casts of all Palmyrene inscriptions taken up by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, which published the first fascicle of their Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum in 1926.

The great temples of Baalshamin and Bel survived into modern times, most likely due to their conversion into churches and a mosque, respectively, and thus were visible to Cassas’s pen and Vignes’s camera.

The religious life of ancient Palmyra was a diverse overlay of belief systems that allowed for civic-wide, social-group-based, and individual worship of the divine. Over the course of the first three centuries CE, Palmyrenes venerated many gods by constructing an array of temples, supporting priesthoods, and representing local divinities in their art. Ritual function of the city's cults has to be deduced from archaeological data since liturgical texts, prayers, and mythological stories are not represented in the thousands of inscriptions found at the site. For example, the long Colonnade Street leading to the Temple of Bel's large altar and ritual basin, both used for animal sacrifice, make evident that grand spectacle was a part of Palmyrene culture.

The great temples of Baalshamin and Bel survived into modern times, most likely due to their conversion into churches and a mosque, respectively, and thus were visible to Cassas's pen and Vignes's camera. Twentieth-century excavations throughout the city have uncovered sanctuaries or references to "indigenous" and "foreign" gods such as Yarhibôl, Aglibôl, Allat, Shamash, and Nabu. Scholars have inferred, through historical and linguistic evidence, that these cults had more connections to Babylonian, Phoenician, Canaanite, and Greek religions rather than Roman—attesting to their Eastward-looking attitude and the cosmopolitan and pluralistic nature of the city's inhabitants. Although a synagogue has yet to be found at the site, Hellenistic sources confirm the presence and importance of a large Jewish population that contributed to Palmyra's multiethnic and multireligious society.

Palmyra's vast cemeteries with multistoried tower tombs and expansive house tombs, holding as many as 400 bodies each, bear witness to the importance that the Palmyrenes—a people of Aramaic descent with strong Arab ties—attached to commemorating the family in the afterlife. Richly decorated with sculptures of the deceased, the massive tombs are the source for some 3,000 bust portraits held today by museums worldwide. Modeling Greco-Roman naturalistic traditions of portraiture, but often draped in native Parthian garments with eyebrows more stylized and incised, as in the Assyrian tradition, these ancient sculptures stare proudly back at us as witnesses of their illustrious history—a history that includes a core, elite group of merchants and traders who along with their indigenous identity enjoyed the ability to use the attributes of other cultures to display their wealth and cosmopolitan status. Removed from their place of origin, the busts bear testimony to the wealth of a vibrant multicultural society, the ravages of time and politics, and the enduring resonance of art.

During the Byzantine, Early Islamic, and Ottoman eras and into the modern period, Palmyra remained inhabited, though the number of citizens dramatically declined.

Throughout much of its ancient history, Palmyra maintained its independence as a protectorate of the Roman Empire. In 212 CE, under Emperor Caracalla, it was elevated to the status of a Roman colony, which it held until 260 CE. In that year, to commemorate his victory over the invading Persian army, the Palmyrene leader Odainat was given the title of Dux Romanorum (commander of Roman military forces) by the Romans, and Palmyra and its surrounding area became a de facto independent city-state. Upon Odainat's death, his wife, the legendary Queen Zenobia, harbored ambitions to expand her control into other Roman provinces, especially Egypt. Though her initial military campaigns were successful, in 272 CE the Emperor Aurelian, a capable general, invaded the city and recaptured Palmyra. This siege and another in 273 CE to put down a second rebellion caused considerable damage to Palmyra's urban fabric, contributed to the city's loss of status as a trading center, and led to its gradual depopulation. In the late Roman period, Palmyra existed as a minor provincial town with a Roman garrison.

Over the following centuries Palmyra lost its Greco-Roman identity, becoming known as Tadmor—a name of Arabic origin that references its position as a desert oasis and its association with the date palm. During the Byzantine, Early Islamic, and Ottoman eras and into the modern period, Palmyra remained inhabited, though the number of citizens dramatically declined. As the city was successively conquered by invading armies or annexed by powerful dynastic states for over a millennium, its civic and religious structures were partially dismantled for reuse as building materials in later structures and fortifications.

After establishing Palmyra as an outpost in his great empire, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian reinforced the city walls in 527 CE. For the next few centuries, the successive Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid Caliphates held the city as a place of trade and a stronghold, fortifying the Camp of Diocletian and building a mosque inside the Temple of Bel. Hamdanid rulers from Aleppo built up defenses in the 10th century to repel Byzantine raids; in the 11th century Syria was conquered by the Seljuk Turks, who vied for dominance in a region beset by Crusaders. The city's splendid ancient monuments were damaged by major earthquakes in the 11th century, with further erosion caused by sand blowing in from the surrounding desert. In the 12th century Turkic leaders based in Homs and Damascus replaced one another, fortifying the Temple of Bel's courtyard. The Ayyubid successors of Saladin's empire constructed the 13th-century hilltop citadel seen in many of Vignes's views. The Mamluks of Egypt and Syria controlled Palmyra until it was sacked and destroyed in 1400 by the Central Asian warlord Timur (Tamerlane). When the site came under Ottoman rule in 1516, only a small village remained in the Temple of Bel, where, as seen in Vignes's photographs, mud-brick houses filled the precinct. By the early modern period, the city that was once ancient Palmyra was unknown in the West.

Previous

City Plan & Monuments

Banner image: